Guru Golwalkar continues to cast a long shadow on India’s polity as his militant Hindutva ideology gains widespread intellectual acceptance and therefore his ideas merit a response. While there was much in Golwalkar’s ideas that were either contemporaneous or acceptable across a wide swathe of intellectual fora, including American academics and nationalists, there’s more to Golwalkar. Golwalkar’s idea of India was founded on racial supremacy and here’s why I call it so and why it needs rebuttal.

Disclaimer:

This blog will appear to suffer from lack of balance or holistic 360 degree view and worse it’d seem I’m attempting a whitewashing of history and the conflicts. Far from it, the idea is to show within a small space the lesser spoken aspects of a very complex and labyrinthine history. The idea is not to paint any one religion as wholly good or evil. Conflicts, many times bloody and tragic, have happened but that’s not the full story. I’ve touched several contentious points in this blog and many need detailed discussion of their own. If a reader feels, at the end, compelled to re-evaluate what he or she thought already knew I’d have succeeded.

Immature Golwalkar Vs the mature Golwalkar:

Golwalkar was nearly 33 years old when he wrote the polemical tract ‘We our nationhood defined’ that outright classified religious minorities as second class citizens. This we’re told was Golwalkar being amateurish in his young years. ‘Bunch of thoughts’ a rambling collection of Golwalkar’s ideas was published in 1966 when he was nearly 60 years old. A chapter is titled “Internal Threats” and the first sub-heading is “Muslims”. The next threat is identified with the sub-heading “Christians”. The leopard could not change its spots.

Golwalkar accuses Muslims and Christians of being not just disloyal to India but practically betraying it. Muslims, he charged, were using secret transmitters and were in communication with Pakistan. Christian missionaries in the North Eastern states, he charged, trafficked in arms procured from America and routed through, who else but, Pakistan.

The septuagenarian leader wrote:

“But the question before us now is, what is the attitude of those people who have been converted to Islam or Christianity? They are born in this land, no doubt. But are they true to their salt? Are they grateful to this land which has brought them up? Do they feel that they are the children of this land and its tradition, and that to serve it is their great good fortune? Do they feel it a duty to serve her? No! Together with the change in their faith, gone is the spirit of love and devotion for the nation.”

His prescriptions for Muslims are simple and echo what he wrote in his youth. Calling upon minorities to “share in the best values of the past” the Guru gives his unambiguous idea of what that past is. “In cultural history, they should all give their mind and hearts whole-heartedly to an appreciation of the best types of Rama and Krishna”. Then he launches on a full scale propaganda, propaganda that is repeated today by many including those who do not agree with Golwalkar or have never heard of him, arrogating to Hinduism virtues of tolerance, classless society (‘No class war’). He also adds caustically, “Nor does it end there. They have also developed a feeling of identification with the enemies of this land. They call themselves 'Sheikhs' and 'Syeds'. Sheikhs and Syeds are certain clans in Arabia.”

To an American who objects that Golwalkar does not treat Muslims and Christians as Indians he retorts “Suppose one of our countrymen goes to America, settles there and wants to become an American citizen. However, he refuses to accept your Lincoln, Washington, Jefferson and others as his national heroes. Would you then call him a national of America? Tell me frankly.”

Golwalkar equates native born sons of Indians to those who emigrate to an alien land. Even if one were to swallow the Guru’s equivocation one could ask him equally if he recognizes the best of Muslims and Christians in India?

Golwalkar equates native born sons of Indians to those who emigrate to an alien land. Even if one were to swallow the Guru’s equivocation one could ask him equally if he recognizes the best of Muslims and Christians in India?

Even today schools runs by Brahmins and Hindutva ideologues stop with ‘Hindu’ culture whenever they speak of ‘Indian’ culture. Unlike Christianity Islam has existed in India as a vibrant cultural force for half a millennia and it doesn't get a mention in not just Golwalkar’s book or Ambedkar’s screed on why Pakistan should be created or other Hindutva ideologue’s writings. What was pardonable in Bharathi or Ambedkar or Golwalkar, due to lack of historical knowledge, becomes insidious propaganda when even today Islamic contribution is denied or completely erased in Hindutva writings.

Reviewing a book by an avowed Hindutva writer from Bangalore, pen name Jataayu, Jeyamohan pointed out that the book, “The Omnipresent Narasingam’, completely omits cultural contributions by non-Hindus.

Swami Vivekananda said that India will have Islam for its hands and feet and Hinduism for its mind. What may be ill-chosen words by the Swami becomes intentional program for national unity in the Guru’s words.

“The Mughal emperors of India”, William Dalrymple wrote of the empire at its apogee, “were the most powerful monarchs of their day—at the beginning of the seventeenth century, they ruled over a hundred million subjects, five times the number administered by their only rivals, the Ottomans.” Such an empire could not exist with no cultural cross pollination between its people. Ambedkar was doing Golwalkar’s work for him when he wrote of Hindu-Muslim relationship that “there was no common cycle of participation for a common achievement. Their past is a past of mutual destruction—a past of mutual animosities, both in the political as well as in the religious fields.” Nothing is farther from the truth.

Hindus and Muslims in the Mughal Era:

While any school student would know of Akbar’s attempts to formulate a new religion, Din-ilahi and anyone with a little more knowledge of history would know that Dara Shikoh, son of Shah Jahan, translated Upanishads into Persian not much is known, in popular narrative, of the depths of interactions between Hindus and the Mughal emperors.

The current Hindu nationalist government makes a fetish of spreading Yoga but rarely mentions what the Mughals did to preserve the knowledge of Yoga. Writing in the occasion of an exhibition about the history of Yoga William Dalrymple wrote in The New York Review of Books, “far from being excluded by the Mughals, Hindu mysticism and its affinities with the austerities of Sufism had been a focus of Islamic interest in India since before the first Muslim conquests of the twelfth century….By the sixteenth century, yoga and the secret bodies of knowledge that were associated with it had become part of the science of government in Indo-Islamic courts”.

Salim, as emperor Jahangir was known earlier, rebelled against his father Akbar and settled down in Allahabad, then called Prayag. Allahabad was, like today, a city vibrant with Hindu culture. Salim commissioned a series of portraits titled ‘The ocean of life’ which was a depiction of yoga asanas by an artist called Govardhan. Govardhan, in turn, was inspired by “Renaissance gospel books brought to India by Jesuits”. This confluence of traditions, Dalrymple observed, might be “implausible to anyone who takes at face value the idea of a clash of civilizations: a Hindu artist painting the first-ever systematic set of illustrations of yogic asana positions, while working for a Muslim patron, and borrowing for the yogis the features of Jesus Christ.”

Muhammad Ghawth, also variously known as Muhammad Ghaws, translated ‘Amrutakunda’, a ‘yogic text about the teachings of Hatha Yoga’, to Persian circa 1550. “The Translator”, the book ‘Religious: Interactions in Mughal India’ says, “not only equated Sufi and Yogi practices, and tried to reconcile their doctrines, but also offered concurrences between yogic teaching and Hellenistic philosophy”. Carl Ernst, the Kenan distinguished professor of Islamic studies at UNC Chapel Hill, has written an important paper on Ghaws’s translation of Amrutakunda (see references).

Munis D. Faruqui writing in the aforesaid book says, “by the sixteenth century, and with the establishment of Mughal rule in INdia, we can point to deeply ingrained views in certain Muslim intellectual circles that Hinduism had core beliefs that resonated with Islam”.

From Humayun to Shah Jahan Mughal emperors had a penchant for astrology and that provided the setting for some very interesting interactions between the Brahmins of Benares and the Mughal Court writes Christopher Minkowski. The ‘jyotisas’, astrologers, had a tangled relationship with Mughals. Amongst the three pandits Minkowski talked about Kavindra, also known as ‘Sarvavidyanidhana, is the most interesting. Shah Jahan, acceding to Kavindra’s pleading, rescinded a tax on Hindu pilgrims to Banaras and Allahabad.

“Culture of encounters: Sanskrit at the Mughal Court” by Audrey Truschke delves deeper into the Kavindra-Shah Jahan relationship. “Kavindra also wrote the vernacular Kavindrakalpalata in which more than half the verses are dedicated to Shah Jahan”.

Jagannatha, Minkowski and Truschke identify in their respective works, was patronized by Jahangir, Shah Jahan and Hindu princes. Jagannatha, in the view of his Brahmin contemporaries, took his involvement with the Mughal court a step too far when he fell in love with a Muslim woman.

In sum, Minkowski notes, “Despite some uneasiness, the learned Brahmins in Banaras recognized the Mughal court as source of patronage and of honors of which they could be proud”

As the Mughal era faded and the Colonial era began under the auspices of the East India Company the interactions between Hinduism, especially Brahmins, oh the Brahmins, and the Colonial regime assumed more interesting proportions.

Colonial Raj as Hindu Raj:

“One of the many anomalies”, writes Robert Eric Frykenberg in “Christianity in India: From the Beginnings to the Present”, a very important book that details the very complex history of Christianity in India, “of the Indian empire was the fact that, in fundamental ways, it was a ‘Hindu Raj’ - even as it was ostensibly under British rule. ‘Hindu’ as a term originally meant anything native to India, whether people, language, custom, or religious tradition”.

In very packed sentences Frykenberg establishes how the Company Raj, with active cooperation of Brahmins, welded the vast and disparate Hindu community into one. “The Company’s own government, on the advice from Brahman servants, took over management of all pukka religious endowments and temples”. “Thus, by fiat, was a vast array of Hindu institutions that were welded together within the imperial apparatus gradually reified under the name of ‘Hinduism’”.

This Hinduism was the “by-product of cultural explorations, and socio-political accommodations, before and during the early Raj”. The apogee of the collaboration happened under reign of Warren Hastings, a man Edmund Burke later impeached of having trampled the Indian people. Hundreds of pundits and munshis were patronized by Warren Hastings, notes Frykenberg, and the tradition culminated in the grandiose efforts of Monier-Williams and Max Muller.

The common understanding of missionary activity, especially evangelism and proselytization, during the Raj is very simplistic and very wrong. The Company, Frykenberg points out, was in India for its markets and profits. “Money-making relationships with local merchants and bankers hardly mixed with missionary purposes, the first Evangelical (Pietist) missionaries had been clapped into jail”. Missionaries were not all cut from the same cloth. Dutch and German missionaries were different from Anglican missionaries.

The Company Raj actively protected Hinduism, often at the expense of evangelical Christianity. Missionaries were prohibited against demeaning Hinduism and were penalized when they did so. Non Christian “notables” of Chennai even thanked the Raj for prohibiting missionaries from erecting a Church and a school near their temple. A petition against the Raj condemned it for “requiring Christian soldiers and sepoys to attend ‘heathen’ festivals’”. The petitioners, led by Bishop Corrie, were reprimanded and many were forced to resign from their posts by the Company.

Evangelical proselytization by Christians and the near wholesale conversion of lower caste Hindus, especially Nadars and Pariahs, created most long standing fissures with Hinduism but Hinduism had only itself to blame for the events that unfolded.

“The company”, Frykenberg explains, “always opposed any formal attempt to open its domains in India to Christian missionaries. For equally obvious reasons, after 1813 it was not anxious to disclose the full extent or import of its close relationships with Hindu religious institutions”. Company officers were mostly Brahmans who took part and oversaw Temple affairs freely and it included the military participating in pujas and sacrifices. The Raj was not just Hindu Raj but, Frykenberg says based on upon prevailing opinion of non-Brahmins, was a ‘Brahmin Raj’.

‘The Pariah Problem’, Slavery and Hinduism:

“Nothing can be more humiliating and intolerable than the treatment that the Pariahs…recieve from the Hindus of higher castes. The Hindu religion has done nothing for them except to prescribe a most abject slavery as the lot for which they alone are fit”. Those were not the words of any anti-Hindu or a colonial official or an evangelist but the editorial of ‘The Hindu’, a newspaper run by Brahmins.

But, Slavery, unlike what most Indians like to think, was no stranger to India and has a long tradition. “Slavery & South Asian History”, edited by Indrani Chatterjee and Richard M. Eaton, gives a sweeping view of slavery in India across the ages.

Daud Ali’s chapter on slavery during the Chola era corroborates what K.A. Neelakanta Sastry wrote in his magnum opus ‘The Cholas’. A common trope in India that unlike Islamic invaders native kings never indulged in loot, pillage or capturing women. Ali notes, “The practice of capturing or forcibly abducting women as part of annual military campaigns in rival kingdoms is well attested. ‘Seizing women’ is a conventional boast in the royal eulogies that cover the walls of hundreds of Chola-period temples”. “Chola meykkirtis are often quite particular about the fate of women…in some instances they were ‘defaced’-their noses cut off”.

K.A.N. Sastry wrote “That a considerable element in the population, especially among agricultural laborers, lived in a condition not far from slavery is clear from the literature of the age. There are several inscriptions which show that the most odious form of private property, property, in human beings, signalized by their being bought and sold by others irrespective of their own wishes, was not unknown. Most of the sales recorded in the inscriptions are sales of persons to temples”.

Use of the word ‘slavery’ to characterize the plight of the Pariahs was often a debated one. Even Sastry demurred that the conditions while ‘not far from slavery’ was not all to bad. C.S. Cole, collector of Chingleput District wrote in the 1870s, “[Madras’s slavery] is slavery under its mildest and most benignant aspect”. Rupa Viswanathan in her book ‘The Pariah Problem’ calls this the ‘trope of gentle slavery’. The Colonial regime undertook a vast study of slavery in the colonies and to satisfy the abolitionists back home the existence of slavery was either underplayed in official records or was plainly denied. Ingrain Chatterjee, Viswanathan cites, called it “abolition by denial”. In this context it is pertinent to remember that until the Colonial era the patchy historical records that exist about slavery and sale of human beings are only those that concerned the properties of the temple. In other words the only historical records, as such as what existed, where only those that concerned the properties of the temple and not about the broad populace. India did not have a tradition of history writing akin to Greco-Roman world.

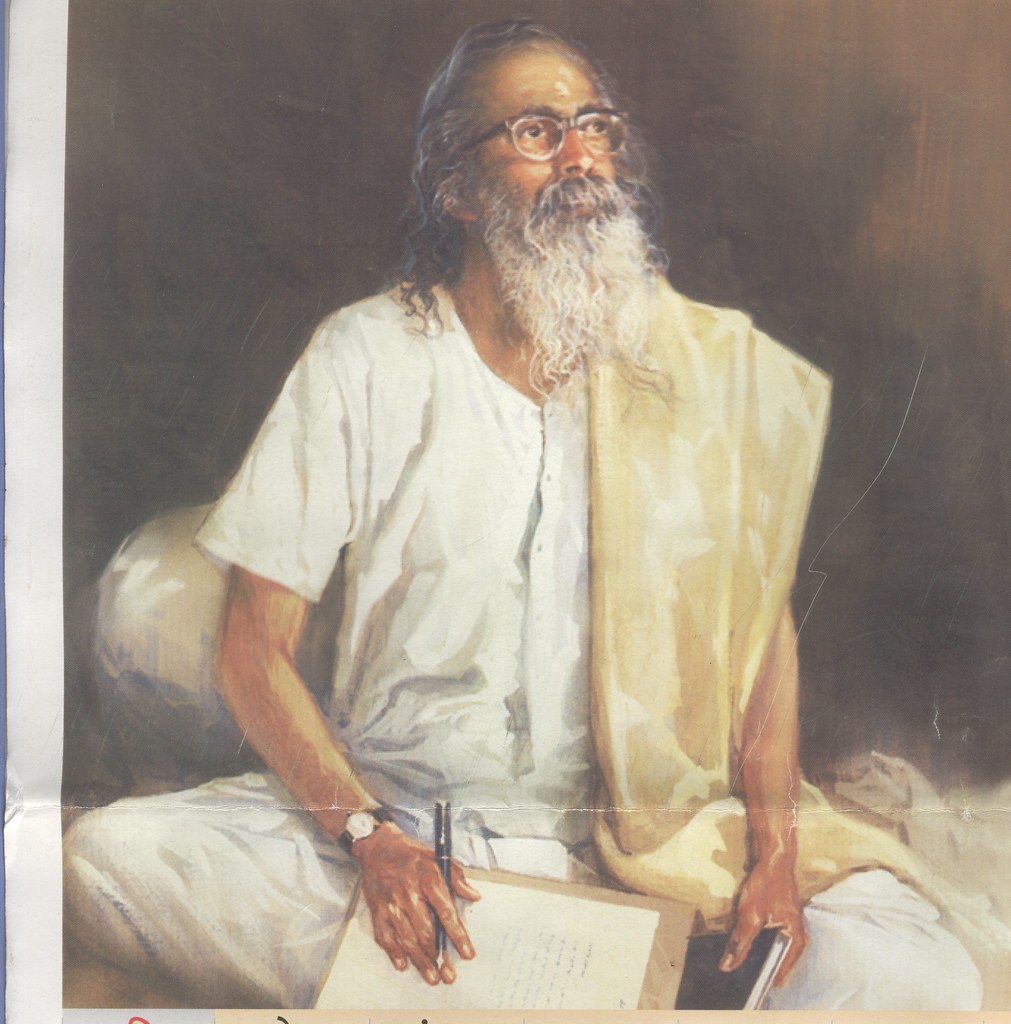

| Observe the picture carefully. |

Recent scholarship is expanding the frontiers how slavery existed in the colonial era from Kerala to North East India.

P. Sanal Mohan’s “Modernity of slavery: Struggles against caste inequality in colonial Kerala” details slavery as an institution in Kerala. “According to the 1836 census, a slave population of 164,864 out of a total population of 1,280,663” existed in Travancore. Nearly one-sixth of Cochin population were slaves. Both landowners and temples freely employed ‘slave castes’. “The centrality of slave labor in the production process is left out even in the most recent Marxist histories of Kerala” says Mohan.

In this backdrop Christian evangelism and conversions altered the fabric of India. “In the 1870s”, Viswanathan writes, “Madras Pariahs took Protestant missions by storm, not simply asking but indeed demanding to be converted”.

Not only Golwalkar but most others too paint a very benign picture of Hinduism as very ideologically open and one that dealt with competing philosophies with purely Socratic debate and devoid of bloody conflicts that characterized Abrahamic religions in the middle east. Absolute and complete bunkum.

Hinduism clashes with Jainism and Intra-religious strife:

Tamil Nadu’s militant atheistic organization relishes in recounting lurid mythical tales about Hindu gods but their twentieth century insults pale into insignificance that Jains and Hindus hurled at each other. Jains taunted Hindus by portraying Siva “as the Offspring of a Jain monk and nun who had broken their vow of chastity”. To the Jains, Paul Dundas says in ‘The Jains’, “The Jains consistently attacked the foundations upon which Hinduism rested”, the Vedas. “Vedas was a false scripture”.

Jain relationship with Buddhists was marked by hostility “throughout the medieval hagiographies which frequently describe great Jain teachers vanquishing the Buddhists in debate or regaining control over holy places”.

Jainism was a vibrant religion in Southern India contributing to its philosophical traditions and literature. Yet, today there’s barely a trace of Jainism in Tamil Nadu. This transition had its share of violence that’s barely recorded but has left traces. A most controversial incident relates to the supposed impalement of 8000 Jains. While there’s little or no proof for that the absence of proof of that incident is not proof of absence of any conflict. Tamil writer P.A. Krishnan ruffled quite some feathers with a column debunking the accusation about impalement cited verses prevalent in Hindu literature that showed how Saivaites, Vaishnavites and Jain freely poured scorn mutually against each other. The verses also freely hinted at retributions.

Violence and militancy was not entirely unknown to Hinduism. David Gordon White’s “Sinister Yogis” and William Pinch’s “Warrior Ascetics and Indian Empires” puts the notion of benign and socratic Hinduism to rest.

Hindutva and even common Hindus hold Christian and Islamic proselytization as ignoble but conveniently forget that Buddhism, Jainism and Hinduism had a past that was built on proselytization. Ambedkar in his ‘Thoughts on Pakistan’ rubbishes this claim of ‘non-proselytization’ past. Ambedkar, with justification, pointed out that Hinduism’s caste obsession and iron framework of caste, at one point, pretty much put a stop to any proselytization. This is also why the recent efforts of Hindutva brigade, to re-convert those who had converted, a complete failure. Those who were invited to come back home had no real home. One can deny all the gods of Hinduism and still be a Hindu but one cannot call oneself a ‘casteless Hindu’. There is no such Hindu, legally and philosophically.

When an Iyengar mother refuses to eat, ever, at her daughter’s home because she married, lo behold, an Iyer or step foot into a Saivite temple we can be sure that differences and conflicts were not always settled with Socratic debate. Well, after all, even in Greece Socratic debate had its limits.

If the distant past left hazy history the much recorded Colonial era laid bare the lengths upper caste Hindus, even after conversion to other religions, would go to treat a section of their brethren as subhuman living beings, nay, as objects that exist only to assert their own place in the hierarchy.

Caste conflict within the church:

Christianity in India developed a unique identity says Frykenberg wherein Christians were at once Christians and retained their Hindu caste identity. From the advent of Christianity in India the caste angle became a problem for both the Church and the Raj to grapple with. It was easier for Hindus to become Christians than to forsake the privileged position they held by virtue of their caste. A riot ensued in 1858 in Tirunelveli (then known as Tinnivelly) when Christians, who were Pariahs, had to take a dead body through streets where upper caste Christians lived.

Vedanayakam Sastriar and Muttusami Pillai, both Vellala Christians from Tanjore, argued that “at the ‘Lords Table’, different communities could only ‘sit together separately’”. Sastriar recorded that in St. Peters Church in Tanjore “European Christians sat on benches, Vellalar Christians sat on fine grass mats, and Paraiyar Christians, low-caste or non-caste people sat on stone floors”. (Note: I’ve attended services in this same church and such practices, thankfully, were ended long ago. I even think the current clergy are from lower castes. I could be wrong). The Church, under the leadership of one Daniel Wilson, excommunicated nearly 3000 Vellalas for insisting on segregation in seating and to drink from a common cup during communion. Note, even today in upper caste strongholds in Madurai Dalits are compelled to use separate cups in coffee shops by upper caste Hindus. And, even today in upper caste Hindu areas Dalits cannot pass through and access crematoriums or cemeteries. Christian or Hindu the caste dominance exists from a millennia ago in India and roots are indisputably within Hindu theology.

|

| The picture says enough about the condition of Dalits |

Two cases that approached the courts of the Raj illustrate very painfully how oppressive the caste dominance was and it was plainly slavery.

In 1923, David Mosse cites a case in ‘The Saint in the Banyan Tree: Christianity and caste society in India”. Maravars and Udeyars approached a court of law to decide whether Pallars had the right draw water from the public tank and if so whether they can use mud pots instead of pots made of palmyra leaves. The judge ruled that Pallars can draw water from the public tank but they cannot, having acknowledged the superiority of Maravars and Udeyars, use mud pots and they should stick to using palmyra baskets. Imagine taking water in a palmyra basket instead of a mud pot (not even a metallic pot, that was unthinkable).

Rupa Viswanath cites a 1910 report in Iyotheethass Pandithar, a Dalit leader and intellectual, run ‘Oru Paica Tamilan’ of a judgment concerning a Pariah who was assaulted for carrying an umbrella. The magistrate ruled “Your holding an umbrella, by going against customary practice, is itself a violation: case dismissed”. In 2013 in a Tamil Nadu town, Vadugapatti, a report in ‘The Hindu’ said, a 11 year old Dalit boy was forced to carry his footwear on his head. The report also said Dalits cannot ride a vehicle, even as passenger, and therefore they have to carry grocery on their head after a market visit. The news report said the Panchayat President, “a caste Hindu, dismissed the allegations as baseless”.

Rupa Viswanath details devastatingly how caste Hindus, converted or not, used the ‘doctrine on non-interference in local customs by the Crown, to scuttle any efforts to ameliorate the difficulties of the Pariahs or any egalitarian effort.

Ambedkar had observed trenchantly, “no society has an official gradation laid down, fixed and permanent, with ascending scale of reverence and a descending scale of contempt”. He summed it in what Christophe Jaffrelot calls a very important sociological formulation, “a progressive order of reverence and a graded order of contempt”. This concept of ‘graded contempt’ is an important reason why Ambedkar, a Mahar, could at no point become a pan-Dalit leader. Even amongst the Dalits the Mahars and Chamars and others held each other in ‘graded contempt’.

A religion which stipulates the vessels one can use, the dress one can wear, the daily habits, the jobs one could seek is essentially codifying slavery. To deny it is sheer racism. Any religion that codified and zelously enforces slavery is a violent religion. It is high time Hindus stopped prattling about Ghazni Muhammad or Nadir Shah. Yes they committed genocidal killing but killings that were, to point out the obvious, were par for the course in the 18th century. On the other hand Hinduism put millions of their own brethren, for generations across centuries, under the yoke of casteist oppression. So please save the lecture of Hinduism being benign unlike its Abrahamic competitors.

The caste conflict within the Church played a large role in Ambedkar deciding to convert to Buddhism.

Conversions that shook Hinduism: Ambedkar and Meenakshipuram

On 14th October 1956 Ambedkar converted to Buddhism and 50,000 followers of his got converted too. Christophe Jaffrelot’s ‘Dr Ambedkar and untouchability: Fighting the Indian caste System’, gives a nice summary of the events leading to the event that continues to reverberate even today.

Ambedkar approached the question of conversion in a very transactional manner. For a time he toyed with the idea of Sikhism. To that end he even suggested that all that needs to be done, to avail educational opportunities that were reserved for ‘Depressed classes’, was to add Sikhs to the list of castes covered by the Depressed Classes so that “who become a convert to sikhism will not lose his political rights he would have had if he had remained a Depressed classes”. By 1947 he had given up on this idea and that he zealously prohibited, with the active support of Sardar Patel, Sikhs from being covered by the Reservation policy that was being framed at that time as part of the new constitution, appear connected.

In a stunningly candid quote Ambedkar evaluates the choices of Islam, Christianity and Sikhism based on who can provide financial resources. Islam appears attractive to him based on numbers and possible resources from overseas. Christianity is less appealing because they’re meagre in number and therefore financial resources could be strained though augmented, as before, from overseas. Sikhism appears at a distinctive disadvantage to Ambedkar. He ends the quote with the famous line “Conversion to Islam or Christianity will denationalize the Depressed Classes”.

Upper caste Christians who were alarmed by the possible swelling of ranks of the lower castes if Ambedkar and Dalits converted to Christianity conveyed, urgently, that they would not be welcome. There is an ugly side to Ambedkar’s choice of Buddhism however.

Moonje, Hindu Mahasabha leader, and Sankaracharya of Karweer Pith worked to dissuade Ambedkar from going over to Christianity or Islam. The Sankaracharya made a telling proposal, “It is futile to coax the so called Sanatanists into agreeing to concede to untouchables their legitimate rights. This revelation promoted me to advise Dr Ambedkar and his followers to stop wasting their energies in trying to persuade the orthodox, and to found a sect of their own, or to go over to one of existing sects of Hinduism which does not flourish on Untouchability”. Note, the Sankaracharya concedes it was impossible to reform Hinduism but only pleads that Ambedkar not abandon it wholesale. This came to be called the Ambedkar-Moonje pact.

It is laughable to see the current Hindutva brigade appropriate Ambedkar and present themselves as egalitarian minded towards the Dalits. Ambedkar after organizing a burning of Manu smriti advised, in preparation for a mass conversion, that Dalits should not participate in Hindu yatras or observe Hindu festivities, At a meeting of Mahars in May 1936 one of three resolutions passed was “as a first step towards conversion, Mahars will refrain from worshipping Hindu deities, observing Hindu holidays and visiting Hindu sacred sites”. Amongst the 22 vows that Ambedkar administered on 14th October were: refusal to recognize the Hindu trinity or to worship them, refusal to recognize Ram and Krishna as gods, refusal to perform any rites through the agency of a Brahmin.

News items published by the Hindu dated July and August 2016 speak of two towns in Tamil Nadu were Dalits were denied entry into temples. It is this religion that we are told subsumed with active and free consent of sects of ‘smaller gods’ into the ‘larger gods’. Bunkum.

On February 19th 1981 a small town in Tamil Nadu shocked Hindu India when 800 Dalits (300 families) converted to Islam. A converted Muslim recounted how they, as Dalits, could never sit on the seats in a bus. Nearly 15 years later when the then government named a bus, yes, just named, after a low caste leader the city of Madurai erupted into violence and a 10 year old boy, with blood shot eyes, told a lady journalist that he’d never step into a bus named after a lower-caste man. Jim Crow laws were not unique to America.

Too much is made of Indian constitution allowing the freedom to not just profess any religious but to propagate it. This freedom to profess and propagate is a fig leaf progressivism because the Indian state, by another rule, puts Dalits of Islam and Christianity as ineligible for reservation benefits, a key social upliftment program that bestows education and jobs. Ambedkar had strenuously argued that reservation should only be based on caste and not on a combination of socio-economic factor and then, much to the joy of Hindtuva brigrade, refused that key benefit to anyonee who converts. One of the Meenakshipuram converts alluded to the loss of such key benefits and said that getting respected as human being in daily life mattered more.

When Tamil Nadu was ravaged by floods in 2015 Dalit colonies in Cuddalore were left to fend for themselves for 36 days. Sure, one could point to how New Orleans was treated during Katrina but the difference is that the Cuddalore episode barely registers in the collective consciousness of Tamil Nadu Katrina is spoken of America’s shame and an exhibition in Newseum, a museum dedicated to news, speaks of it. Even more recently Dalit students in a government school in Rameswaram were asked to clean septic tanks and the incident was barely reported. Societies suffer from iniquities but I’d anyway consider a society that at least talks about it openly as offering better hope than one in which iniquities are swept under the carpet.

The absence of a Herodotus or a Thucydides in India is not accidental. Indians love to glide by facts and look at recording facts as an inconvenience to Trumpian narratives of ‘alternative facts’. Hindutva brigade often laments that Indian school children do not learn history properly. True, if they were to learn it properly they’d learn agout Meenakshipuram and how 42 women and children were burned to death for the sin of asking meager wage increases and how it took nearly 25 years for a single documentary to emerge about such a shameful event in which none were convicted.

A group of Hindus settled in England have petitioned Theresa May that they would oppose extending anti-discrimination laws to caste based discrimination. A British Hindu went so far as to claim that such discrimination does not exist and what may happen is occasional “taunting” of other castes. If this is the opposition put by Hindus in today’s England one can only imagine the gravity of the injustices of the past.

Golwalkar’s idea of India and Nehru’s India:

From Bharathi to Annie Besant and Golwalkar and even the Congress what was often presented as Indian culture was mostly Brahminical. Bharathi presented Vedic India as the ideal. Under the Congress and in many Brahmin institutions even today ‘Indian culture’ is often taken to mean ‘Brahmin Culture’ or ‘Hindu Culture’. I’ve studied in Brahmin institutions and those institutions showed a complete blindness to anything not Brahminical. Annie Besant too presented Brahminism as Indian culture and sowed the seeds for a virulent and very militant anti-brahmanism by the rich non-Brahmins of the then Madras state. The virulence continues unabated even today. While on the one hand the fact that Hinduism was less monolithic than Abrahamic religions is pointed to as a matter of pride Hindus have yet to learn the art of providing cultural space for the many voices in an egalitarian manner. Differences are more often muted than celebrated.

Golwalkar facetiously looked at India’s minorities as akin to immigrants and cooly denied that they could have shaped their own cultural and intellectual contributions, and symbiotically coopting the native culture while influencing it in return.

Ironically Hindu immigrants in US enjoy precisely the rights and liberties that Golwalkar wants to deny India’s minorities. Hindu associations in mega corporations celebrate Diwali as company sponsored events while in those same companies Christmas trees are referred to as Holiday Tree. When Hindu customs run foul of local laws, example people dumping Vinayaka idols in rivers, local law enforcement, instead of throwing the law at them, engages with the community and tries to figure out a solution amicably. America also gives a California based Hindutva bigot to abuse and debase Christianity, a freedom that Golwalkar would never give unto India’s minorities. Put simply, by Golwalkar’s standards many Hindu Americans could easily be called disloyal but no American in his rightful senses would do that.

A Hindutva group was furious that Indian Muslims while not participating in donating organs after death, due to religious reasons, nevertheless are recipients of donor organs. They suggested that such Muslims should be denied organs. A barbaric and uncivilized argument that only the sick minded could make. Scores of Hindus indulge in native treatments, that pass for Indian culture, and then show up at the door step of a doctor educated in Western medicine and expect to be treated. Indian government, at federal and state level, spent thousands to spread awareness about vaccines, family planning, treatment for small pox etc all of which were considered religious taboo for Hindus. What the Muslim community needs is education not ostracism. However, where does the root of such barbaric suggestions lie? It lies in the Golwalkar and Ambedkar idea of looking at minorities as ‘foreigners’.

Whenever the Dalit oppression issue is raised we’re often told that Hinduism will take care of its own internecine problem and others need not bother. But when a problem involves minorities the attitude of “we’re in this together” goes out of the window and the “here’s a foreigner” attitude rules the roost.

In my earlier blog I had argued, with evidence, that many of Golwalkar’s views were not out of line with what even some like Gandhi, Vivekananda, Ambedkar, Subash Bose, Samuel Huntington and Pat Buchanan espoused. Notably the name missing in that list is Jawaharlal Nehru.

Unlike Bose and Golwalkar Nehru had not only complete detestation of the Nazi regime he understood precisely the nature of that regime. Nehru also understood, as early as 1938, that when World War comes Germany, Japan and Italy will join hands together. Not even Churchill was so clairvoyant. Unlike Moonje Nehru had not only no fascination for Mussolini he even refused to meet Mussolini. Nehru was too much a liberal and an aristocrat to pat the shoulders of a fascist thug.

Gandhi, Ambedkar, Patel amongst others have uttered unflattering opinions of other castes and races but amongst the many volumes of Nehru’s writings there’s not a single sentence that’s racist or casteist or xenophobic. This is an exception of mega-proportions given the age he lived in.

Golwalkar laments that Zakir Hussain visiting a mosque is no issue while a furor ensues if V.V. Giri goes to a temple. Such frivolous charges have been used from his days to the day L.K. Advani tore into the Indian heartland with his rath yatra while lambasting secularism, as it is practiced, as pseudo-secularism. Golwalkar and Advani were trying to discredit the very notion of secularism as a principle based on how some mistakes had happened. Let’s not forget that for all such brouhaha what is truer is that from government offices to ministries open celebration of Hindu festivals, exclusively and at tax payer expense, is par for the course.

The Hindutva fascination for Zionism and Israel is half-baked. Theodor Herzl, the father of Zionism, stated “Every man will be as free and undisturbed in his faith or his disbelief as he is in his nationality. And if it should occur that men of other creeds and different nationalities come to live among us, we should accord them honorable protection and equality before the law”. Sadly, Israel has fallen far short of that ideal for reasons of their own and situational. Anyway, Israel’s problems and solutions are Israel’s own. Israel is not and never should be a model for India on race relations. At least not in the way the Hindutva brigade intends. There is considerable angst amongst international Jewry about the direction of Israel. Check out “My Promised land” by Ari Shavit. There are other lessons India can learn from Israel, like its culture of innovation. Check out “Start up Nation: The story of Israel’s economic miracle”

Nehru, of course, was no crude secularist and to him everything mattered. Whether it was Rajendra Prasad going to inaugurate the rebuilt Somanatha temple or P.D. Tandon, a Hindu fundamentalist, being nominated for Congress President post. Given the searing wounds of the partition Nehru wanted India to be secular in law and spirit.

Nehru is often accused of being an internationalist at the expense of nationalism. Its more appropriate to say that Nehru was the finest liberal democrat both in his time and thereafter. Even amongst his peers across the globe there were none who imbibed the principles of liberalism as a political order as Nehru did. To Nehru liberalism was a moral and political necessity for India to survive. Speaking in the Parliament on 9th August 1950 Nehru, echoing what Churchill said of how Britain would fight the Nazis, stated, “They put us in a position in which we have to say to people who are our fellow citizens, ‘we must push you out because you belong to a faith different from ours’. This is a proposition which, if followed, will mean the ruin of India and the annihilation of all that we stand for and have stood for. I repeat that we will resist such a proposition with all our strength, we will fight it in the houses, in fields and in market places. It will be fought in the council chambers and in the streets, for we shall not let India be slaughtered at the altar of bigotry.”

India, if it has to progress, should rededicate itself, everyday to Nehru’s vision of India. There is hope. At Pappappatti, a village in Tamil Nadu, once Dalits who contested and won Panchayat Board elections were murdered by upper caste Hindus but recently amity has been established and Dalit Panchayat President was given a rousing reception by upper caste Hindus. During the December 2015 floods Muslims in Chennai cleaned temples and provided food to Hindus. Gandhi and Nehru understood this India and it is this India that they gave their heart and soul for.

References:

- The Pariah Problem: Caste, Religion, and the social in modern India - Rupa Viswanath

- Christianity in India: From the beginning to the present - Robert Eric Frykenberg

3. The Saint in the Banyan Tree: Christianity and caste society in India - David Mosse

4. Dr. Ambedkar and Untouchables - Christophe Jaffrelot

5. The uprising: Colonial State, Christian Missionaries, and anti-slavery movement in North-East India 1908-1954 — Sajal Nag

6. Slavery and South Asian History - Ed. Indrani Chatterjee and Richard M. Eaton

7. Modernity of slavery: Struggles against caste inequality in colonial Kerala - P. Sanal Mohan

8. The Jains - Paul Dundas

9. Sinister Yogis - David Gordon White

10. Warrior Ascetics - William Pinch

11. The Cholas - K.A. Neelakanta Sastry

12. Herzl’s Vision: Theodor Herzl and the foundation of the Jewish State -- Shlomo Avineri.

13. My Promised Land: Ari Shavit

14. Startup Nation: Israel’s Economic Miracle — Dan Senor and Saul Singer

15. Culture of encounters: Sanskrit at the Mughal Court” - Audrey Truschke

16. Religious Interactions - Ed. Vasudha Dalmia and Munis D. Faruqui

Links:

Dalits and Temple Entry in Tamil Nadu http://www.thehindu.com/news/Dalits-and-temple-entry-in-Tamil-Nadu/article14545908.ece

Kallimedu issue http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/Caste-Hindus-may-let-Dalits-host-festival-at-Kallimedu/article14548771.ece

http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/they-dare-not-wear-footwear-here/article4795453.ece

Poetry of Kings: The Classical Hindi Literature of Mughal India (Kavindra Shah Jahan) https://books.google.com/books?id=CmaItUIsB2AC&pg=PA151&lpg=PA151&dq=Kavindra+Shah+Jahan&source=bl&ots=ytFXPC9f2q&sig=V_KP86LHmFblHpqYMtdoXjaoD98&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjA8M30t8HVAhVk9IMKHdzEC8sQ6AEIJjAA#v=onepage&q=Kavindra%20Shah%20Jahan&f=false Pg 151